CTwik : General Purpose Hot Patcher For C++

Introducing CTwik, a tool for general purpose hot patching in a C++ process.

CTwik enables developers to hot patch their C++ code change, to a running C++ application, without even restarting the application.

CTwik-client comes with a directory watcher, which automatically keeps on figuring out the code change anywhere in repo, compute diff, and figure out the minimal set of functions which needs to be recompiled for patching.

CTwik-server, which must be running in a dedicated thread in the main C++ Application, receive the patch request from CTwik-client and dynamically inject the patch at runtime, by changing the machine code of current-process (itself) to reflect the behaviour change of App, as per the changed code.

CTwik can take care of almost any kind of code change, including the change in header files, function signatures, struct/class layouts, global variables, class layout of global variables, local static etc.

CTwik typically takes a few seconds for end to end patching, after the code change is saved in text-editor.

Why do we need hot patching ?

- As we know that, a typical development cycle involves code change locally, recompiling/rebuilding the entire App, publishing the executable to target machine, restarting the App, waiting for the App to be in ready state, etc.

- App restart will loose in-memory state.

- App restart brings App downtime.

- App restart can a lot of time, sometime minutes, which becomes bottleneck in developer’s productivity.

- Rebuilding the entire App can take minutes, when dealing with big projects, which have executables of size 200MBs.

- With hot-patching, we can skip all these steps within a few seconds

Where else CTwik can be used ?

- Hot patching bug fixes to long running Apps in production.

- Hot patching security fix to long running operating systems or Patching the new version of OS on top of previous one.

- Live debugging on a customer cluster without restarting services. Check the values of some internal C++ variables by patching a function which prints some info.

- And many other use case can be served with hot patching.

State of the art in hot patching

- Hot patching is trivial for Python. There are many tools for hot patching. Also, one can write their own hot patcher in 100 lines because of REPL (exec and eval) in Python.

- Hot patching is a bit hard for Java. Still there are couple of open source tools, which enables to hot swap a a Java class, because of JVM layer.

- Next to Impossible in C++. There are no general purpose hot patcher for C++ which work reliably, for Application in production environment, without requiring developer having to know about their internal detail and requiring a lot of custom handling in code.

Hot Patching is hard in C++, because once the App starts, there is only machine code, which runs directly on the hardware. There is no software abstraction to control it, unless we change the machine code itself of currently running process.

Why CTwik

- CTwik is a novel invention to implement general purpose hot patching, which covers 99% of the typical code changes. The major change it doesn’t cover, are the change in the ‘main’ function and other top level functions which are above user’s API handlers. Those top level boilerplates are rarely changed over time.

CTwik Implementation Summary

- There are two parts of CTwik - Client and Server.

- Client deals with C++ code diff and extracting out the minimal set of functions which needs to be recompiled and create a shared library of changed functions.

- Client also read the shared library using ELF reader, to extract the function symbols and their corresponding function pointers (Memory address in machine code section where the function definition starts).

- Client sends the binary content of shared library and other metadata over TCP request.

- CTwik-Server dump the received binary content of shared library in a file, and open it using “dlopen”, figures out the new definition (new function pointers) of the patched symbols.

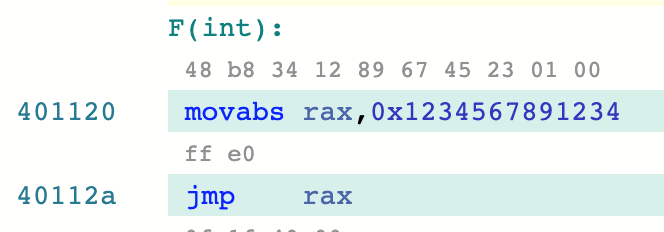

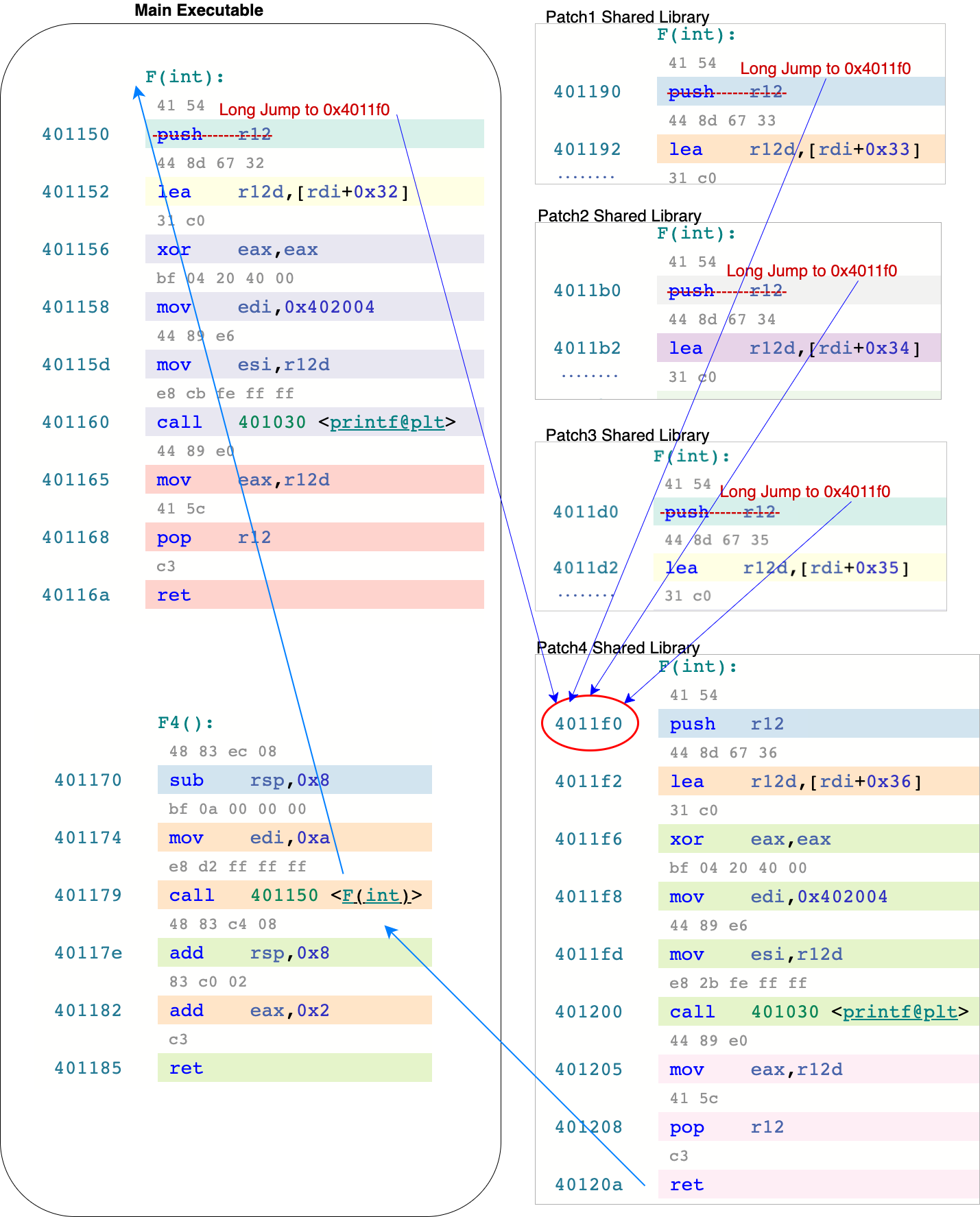

- CTwik-Server change the machine code of current process, to redirect the old function definitions, to the new definitions (new function pointer). This is supported only for x86-64 machines. To redirect, we overwrite the first 12 bytes in the old function definitions, to new instruction “long jump to new fn ptr” (moveabs %rax 0xVV ; jmp %rax). Here ‘0xVV’ is the 64 bit new value of function ptr.

- [Beta Implementation] For global data symbols, we change their entry in global offset table, so that old functions (including the unpatched), will be referring to their new value from shared library. To support this, entire application code needs to be compiled with ‘-fPIC’ option.

CTwik-Client Implementation Details

Let’s understand the ‘extracting minimal set of function’ piece with an example. Consider a translation unit (TU) ‘file1.cpp’ containing following code.

// file1.cpp

#include <stdio.h>

void G( ) {

...

}

int F(int x) {

x += 50;

printf("x = %d\n", x);

return x;

}

void P( ) {

...

}

int F2(int x) {

return F(x) + 2;

}

// 100 more functions...-

In this translation unit, if some code is changed in function F (let’s say 50 is replaced by 51), we have to recompile F and F2. The reason why F2 needs to be recompiled, is, F2 can access the implementation of F, and hence F’s definition could be inlined in F2, and the machine code of F2 might not be calling F.

-

To compile F and F2, we need ‘printf’ declaration as well. Hence, the minimal set of code that needs to be recompiled, would be ‘minimal_change.cpp’.

// minimal_change.cpp

extern "C" int printf(const char *format, ...);

int F(int x) {

x += 51; // Changed value.

printf("x = %d\n", x);

return x;

}

int F2(int x) {

return F(x) + 2;

}- In this particular example, it can be observed that recompiling the file1.cpp after changing 50 to 51, will produce the exact same machine code, except for the function ‘F’ and ‘F2’. Hence ‘F’ and ‘F2’ are the minimal and sufficient set of functions which needs to be recompiled, and hot patching the new definition of ‘F’ and ‘F2’ will make the live C++ process behave equivalent to how it would behave if we could have rebuild the main executable again and restart the process.

How to figure out minimal set of functions automatically ?

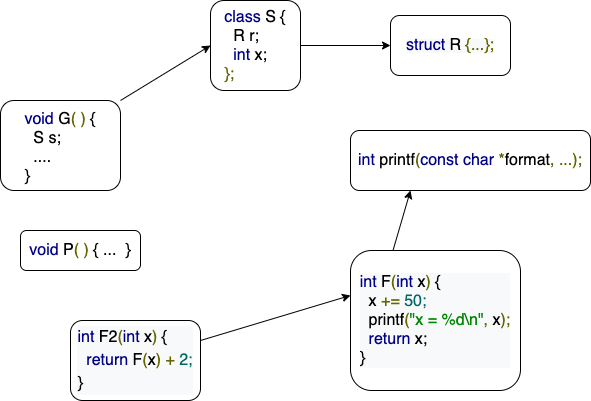

CTwik parse a translation unit (after preprocessing) into graph of global entities. A global C++ entity is a global definition or declaration. An entity could be anything like struct, class, function declaration, function definition, typedef, global variable declaration/definition etc. Each entity declaration / definition introduce a name for it, which can be referred in other entities. For example - struct S { … }; is an entity with name “S”.

int F2(int x) { return F(x) + 2; }is an entity with name “F2”. Globally defined int x = 5; is another entity.

Note that:

- we are not considering the entities inside function-scope. The entire body of a function definition is considered as single entity.

- Each entity has a name. There could be multiple entities with same name (example function overloading etc.)

- Entity name is the fully qualified name of an entity w.r.t. namespace.

Dependency Edge

In the entity graph, there is an dependency edge from entity B to entity A, if entity B refer the name of entity A and entity A is defined/declared before entity B. In case of multiple entity with same name, there will be dependency edges to all such entities.

This is a part of sample dependency graph for above example file1.cpp, assuming class S and struct R are coming from <stdio.h>. Note that this diagram only covers relevant nodes. There will be a lot more nodes/entities in this graph, coming from <stdio.h>.

Minimal Set of Functions

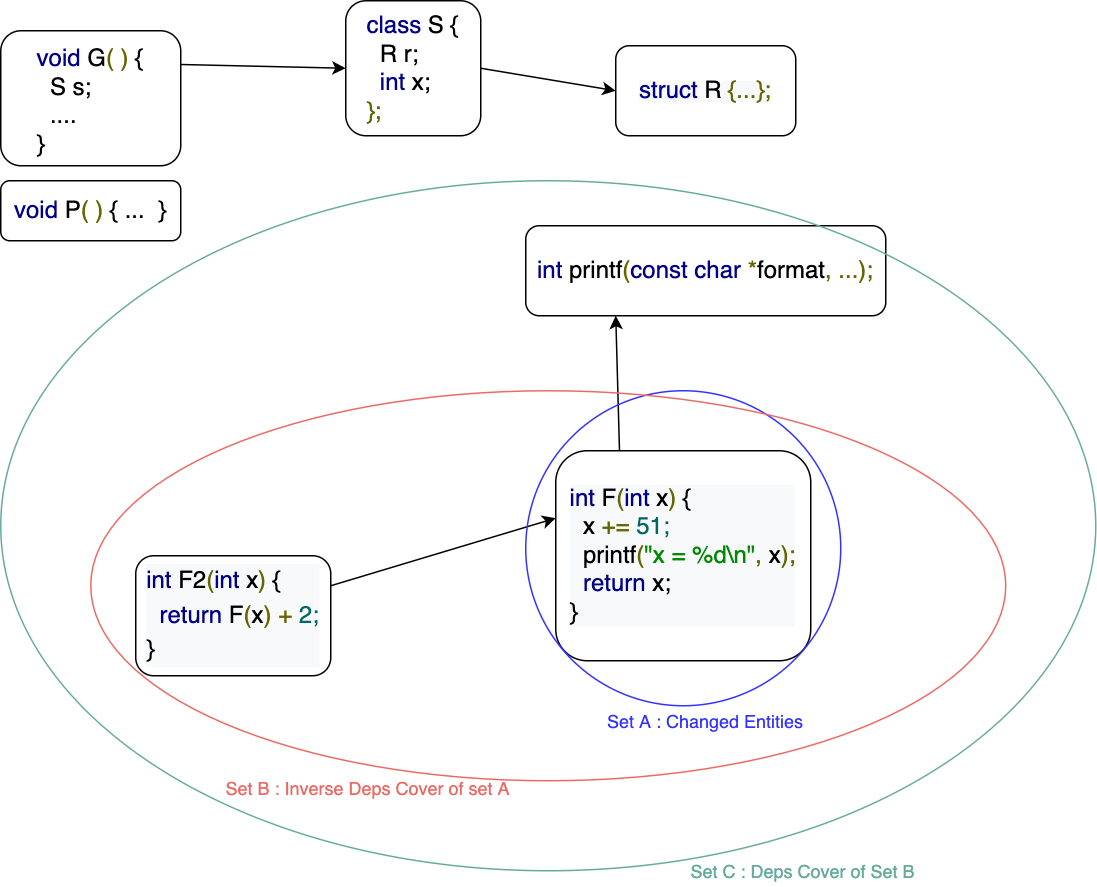

- By computing this entity dependency graph for a translation unit, before and after code change, CTwik figure out the changed nodes of this graph. This can be done by computing checksum of content, for each node, and running diff calculator algorithm on list of entities.

- Let set A = collection of changed nodes or newly added nodes in this dependency graph.

- Let set B = inverse dependency cover of set A. This include all the entities, which were dependent on any of the entity of set A. The set B could include function definitions. Hence we need to recompile them all because some of their dependency (A) is changed.

- Let set C = dependency cover of B.. We need to include whatever is required to compile functions in set B. For example, we might need a struct/class layout for a function to compile, we might need function declaration. etc.

- The set C will contain the minimal and sufficient entities to cover the required functions and dependency entities, required to recompile those functions.

- The last step is to dump the entities from set C to a file

minimal_change.cppin topologically sorted order, and compile the minimal_change.cpp file, to produce the shared libraryminimal_change.so.

Note that:

- Deps Cover (Dependency Cover) of set X is the transitive closure of dependency relationship. Formally,

- DepsCover(X) = Union of DepsCover(x) for each node x in set X..

- DepsCover(x) = {x} + Union of DepsCover(y) for each y in direct dependencies of x.

- Similarly, Inverse Deps Cover (Inverse Dependency cover) of set X is transitive closure of inverse-dependency relationship. Inverse dependencies of node x, is set of nodes/entities which depend on x.

Changing a header file (eg: file1.hpp )

The algorithm described above, to extract the minimal set of entities to recompile, is applicable only for code change in one cpp file, which is preprocessed to make only one translation unit. However if the header file is changed, N number of cpp files (translation units) could be impacted. To handle the change, CTwik computes minimal set of functions to recompile, for each of the impacted translation unit. Each of the minimal_change_1.cpp, minimal_change_2.cpp, … etc. file is compiled to .o object files individually and then linked together to produce shared library minimal_change.so.

Note that:

- CTwik client maintains the file dependency graph as well, to enable efficient computation of impacted translation units, when a header file is changed.

- CTwik client keeps the entity dependency graph in cache, when a translation unit is changed for the first time.

- The entity dependency graph also includes the original file where the entity has been declared/defined. (Entities in a TU could be coming from many headers). This allows CTwik to efficiently extract the impacted entities across large number of translation units, when a entity is changed in very base level header file, which is

#include‘d in a large number of TUs (directly or indirectly) but only few of TUs are really using the changed entity from that header. This is a big optimization when the code from very base level header is changed.

Invalid code change

What happens when, there is a.hpp file, containing int F(int x); declaration, and a.cpp file, containing it’s definition. Another file b.cpp is using #include "a.hpp" , and calling F(int x) inside function “F3”. Now if F(int x) is changed to F(int x, int y) in a.hpp as well as a.cpp but not in b.cpp. What will happen ?

- Entity “F” is changed in hpp, hence the functions where “F” was being used in

b.cppwill be extracted out for recompiling. Which will fail to compile, as expected. Hence invalid code change will fail at the CTwik client only. This prevents the risk of invalid code corrupting the running C++ process, when it’s dynamically patched. - Note that, if

int F(int x);is changed tovoid F(int x);ina.hppanda.cppbut not inb.cpp, and if we patch only the new definition of “F”, without patching “F3”, then execution of “F3” function can crash at runtime. - But since CTwik-client correctly report the compilation errors, there is no risk of invalid change being patched in running C++ process.

As per the algorithm above:

1). what happens when a new member is added in a class S:

- All the functions referring to that class S, across all translation units needs to be extracted out in

minimal_change.cppfile. All the global variables referring to S needs to be recompiled. This include global variables of type S, as well as those using S in initialisation value.

2). what happens when signature of a function is changed:

- All the functions referring to the changed function name, across all TUs needs to be extracted out and recompiled.

3). what happens when a new overloading is added for an existing function name “F”.

- Even then all the existing usage of “F” needs to be compiled. This is because CTwik creates dependency based on name of entity. Hence all the entities with name “F” (all overloading of “F”) are the dependency entity for the functions where name “F” is being used.

4). What if “F” is redefined with different meaning in different namespace ‘a’.

- CTwik use fully qualified entity names. Hence “F” and “a::F” are two different entity names, so they won’t interfere with each other.

5). what happens when signature of class member function is changed:

- Currently the entire class declaration is considered single entity, hence all entities across all TUs, referring to that class needs to be recompiled.

- This is actually unnecessarily recompilation, because since the layout of class is not changed, the entities which don’t use that specific member functions (changed one), are not required to be recompiled.

- In future, CTwik-client will create 1+N entities for a class or struct. 1 for class layout, and N for each of the member functions.

6). What happens when definition of class member function is changed.

- Very same thing, that happens for independent functions. Class member functions are also independent functions, with 1 extra parameter for implicitly capturing the class/struct object.

7). Why does CTwik patch only functions and global data. What about other C++ entities ?

- For the purpose of assembly code, there are only 2 kind of entities, functions and global data. Rest other C++ entities are for helping some functions to compile or to produce functions themselves. For example, template, lambdas etc.

8). What happens with static member function of a class

- Static member function of a class are just class-namespace’d global functions.

9). What happens when the initial value of a global variable is changed

- As per the minimal entity extraction algorithms, the global variable will be extracted out in

minimal_change.cpp, and while hot patching, Global offset table for that data symbol will be changed, to point to new memory address in shared library. Hence all the functions in main executable referring to that global variable, will be referring to new variable. - This data object will be initialized (constructor will run on it), before

dlopenreturns. Hence this new object will be valid to be used by all the old functions which were using it. - The old state of this variable will be lost, since it’s constructed again.

10). What happens when layout of class of a global variable is changed.

- Adding/deleting/editing data members in a class can change it’s layout. This will trigger the global variable definition to extract out in

minimal_change.cpp. Also, all the functions across all TUs, where this global variable is being used, will be recompiled because they are in the inverse dependency cover of variable declaration entity. - The data object will be initilized (constructor will run on it), before

dlopenreturns. All the references of this variable are within theminimal_change.so, there is no need of changing the GOT entry of this symbol in main executable, but still CTwik change the GOT old entry to remain safe side.

11). What happens when data-type of a global variable is change from A to B.

- Very similar effect as changing layout of type A.

12). What happens when a global variable or a functions is deleted

- Deletion has no effect, apart from triggering the recompilation of entities, which were previously dependent on deleted entities. If those dependent entities are not fixed (changed) to not use deleted symbol anymore, CTwik-client will fail at compilation step (‘Error: usage of unknown variable/function’).

13). What happens when global variable is renamed.

- This is equivalent of deleting the old one and adding a new one.

14). What happens when layout of a variable’s class is changed, which is used as static local in some function F.

- This will trigger function F to recompile. The compile “F” is a new function now in shared library. After hot patching, old “F” will be redirected to new “F”. Note that if static local variable might be already constructed when old “F” was called first time. That old instance of static local variable is lost now. When new “F” is called for the first time, a new instance of static local variable will be constructed again.

CTwik-Server implementation details

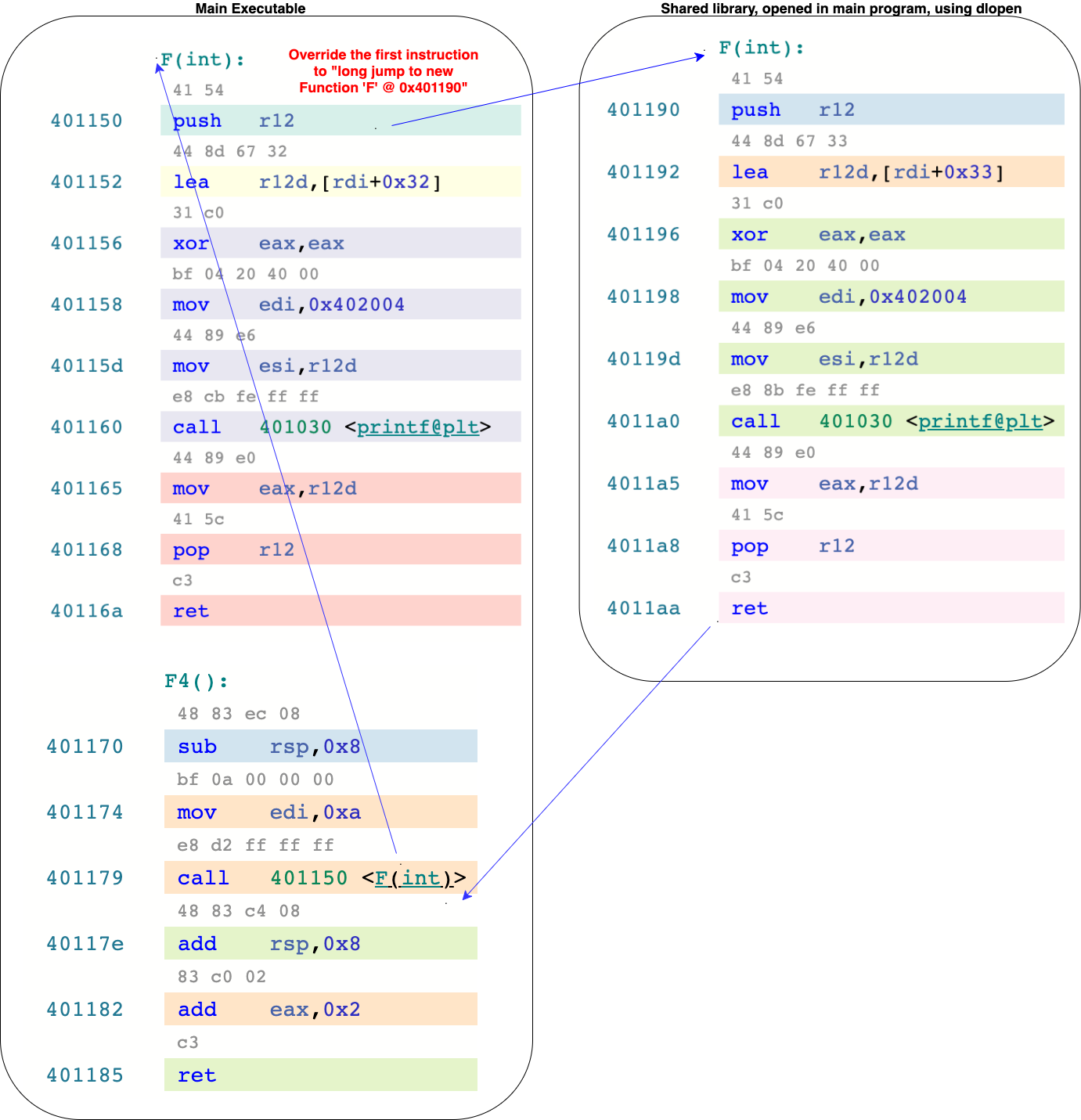

CTwik-Server open the shared library using dlopen and edit the machine code of current process, to redirect (long jump) the old function definitions, to the new definitions (new function pointer).

Let’s consider an example, where function “F” is changed.

Source code for main executable:

|

|

|

After the change:

// Changed file1.cpp (50 is replaced by 51)

#include <stdio.h>

int F(int x) {

x += 51;

printf("x = %d\n", x);

return x;

}

void P( ) {

...

}// Extracted minimal_change.cpp

extern "C" int printf(const char *format, ...);

int F(int x) {

x += 51;

printf("x = %d\n", x);

return x;

}Hot Patching:

Note:

- In this example above, old function “F” is redirected to new function “F”.

- As we are overwriting first 12 bytes of old function “F” to long jump, we are not touching the return-address register, hence, when new “F” returns, code flow will directly go to caller of old “F”, which is “F4” in this example. This is similar to tail call optimization.

- We need long jump because the absolute value of function pointer in shared library could be 64 bit long. In x86-64, long jump require 12 bytes -

moveabs %rax 0x401190 ; jmp %rax. - Note that code section of an address space is not writable by default. We need to make it writable, explicitly using ‘mprotect’ as follows:

mprotect(page_start_ptr, page_size, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC);Changing the machine code

// Change the machine code of function @fp1, to long jump on

// function @fp2.

// It requires following 2 instructions.

// 1. movabs %rax,0x1234567891234;

// 2. jmp %rax;

// Where 0x1234567891234 is the fp2.

// See the machine/assembly code of "F" here:

// https://godbolt.org/z/zKnzjE6x9

bool RuntimeInjector::SetRedirect(long fp1, long fp2) {

if (not AllowWriteInPage(fp1)) return false;

auto fp1_b = bit_cast<char*>(fp1);

Store<char>(0x48, fp1_b);

Store<char>(0xb8, fp1_b + 1);

Store<long>(fp2, fp1_b + 2);

Store<char>(0xff, fp1_b + 10);

Store<char>(0xe0, fp1_b + 11);

return true;

}This redirection is similar to how this “F” (left) is compiled to machine code (right). https://godbolt.org/z/zKnzjE6x9

|

|

How to find old and new function pointers

- CTwik read the symbol table of main executable and patched shared library to get the list of all function pointers and their symbols. Note that “function pointer” is the memory address, where machine code of a function starts.

- In case of main executable, the value of function pointers present in symbol table are the real virtual memory address, where machine code of those functions starts.

- However in case of shared library, the value of function pointer, present in symbol table is the relative function pointer. This is because, a shared lib is loaded dynamically at runtime and the absolute value of function pointer would depend on the memory address where shared library is loaded by

dlopen. - In case of shared library, CTwik-client compute the list of function symbols and relative function pointers by reading the shared library, and send this list to the CTwik-server. This is to optimize the compute in the main C++ process, which is already serving other user facing requests.

- To compute absolute function pointer for all the symbols in patched shared library, we could use “dlsym” for all symbols, but it can impact the performance. Hence CTwik-server calculate the absolute function pointer of only one of the function-symbol, using “dlsym”, and then calculate offset by comparing it’s relative function pointer, and then apply this offset for other function pointers. This require only one “dlsym” call. Calling the “dysym” for all the symbols might impact the performance of hot patching.

- For a shared library, CTwik only considers “.text” section of ELF file, for finding the patched function pointers and symbols. Other code section of ELF are not considered. This is because, only the “.text” section contains user created functions.

Continuous patching

- The CTwik-client can keep on sending patches one after another. The CTwik server need to handle them well.

- CTwik server maintains a map(symbol -> list of function ptr), which tracks all function pointers for symbol S. For example, if a function “F” was present in main executable, and then it was later hot patched 3 times, then this map will contain all 4 function pointers in the map for symbol “F”.

- When a function F is hot patched with new definition, CTwik-server redirect all the existing function pointer of F, to the newly patched definition of F.

- Note that, redirecting the last function ptr to the new function ptr would be sufficient for correctness but it will waste N instructions at runtime when F is called.

- For each of the opened shared library, CTwik-Server keep track of the symbols which are still active (i.e. the symbols, which are not hot patched in the latest patch request). When there is no active symbol, the CTwik-Server dlclose those shared libraries.

Safety consideration in Hot Patching

- Thread Safety

- CTwik-Server requires that, while it’s hot patching a set of functions, none of those functions should be in call stack of any of the thread. The behaviour of CTwik-Server is undefined if this precondition is not met.

- Hence, hot patching needs to be done with write-mode in a read-write mutex at the top level user API handler. i.e. while CTwik is hot patching, all new user APIs should be blocked on a mutex until hot patching is finished. Also, while some user APIs are still being served, CTwik hot patcher should wait for them to finish (acquiring read-write-lock in ‘write’ mode).

- Don’t use CTwik for code change in ‘main’ function or other top level functions, above the read-write mutex.

- We need to ensure that machine code of every function has at least 12 bytes. This is because we need to overwrite first 12 bytes, and if the function body ends before 12 bytes, we might end up corrupting the machine code of next function.

- Currently, GNU linker add the padding in functions to ensure the length of it’s machine code definition is multiple of 16. This is done by adding unreachable “nop” instructions. As a result, even for function like void F() { }, the machine code takes at least 16 bytes.

- The main executable must be linked with ‘-rdynamic’ linker flag. This allows dlopen to succeed, when a shared library need weak symbols from the main executable.

- The main executable must be linked with ‘-Wl,–whole-archive’ linker flag, so that linker doesn’t omit some of the unused symbol definitions. This is useful when some of the functions in shared library might depend on those omitted symbols.

- The hot-patch requests are served sequentially.

Optimizations

- Dealing with function symbol c-string can impact performance. Hence we deal with 64 bit checksum of function symbol c-string. The CTwik-client sends the 64 bit checksum of symbols to hot patch, along with their relative function pointer.

- The map from symbol -> list of function ptr, also use the 64 bit checksum (int64_t) for symbol.

- Note that we don’t need to construct the symbol string again, hence just maintaining the checksum is sufficient.

- CTwik use google’s city hash algorithm for computing check of symbol c-string.

- Note that CTwik-client still need to send symbol string for one symbol, so that “dlsym” can be used on it for figuring out the absolute function pointer and the offset.

The Core Hot Patcher

bool RuntimeInjector::Inject(const InjectRequest& inject_request) {

CHECK(init_done);

static int filename_counter = 0;

string shared_lib_name = "/tmp/ctwik_requested_lib_" +

std::to_string(filename_counter++) + ".so";

quick::WriteFile(shared_lib_name, inject_request.shared_lib_content());

auto patch = dlopen(shared_lib_name.c_str(), RTLD_NOW | RTLD_GLOBAL);

if (not patch) {

std::cout << "Failed to dlopen the patch: " << dlerror() << std::endl;

return false;

}

if (inject_request.symbols_size() == 0) return true;

long fn_ptr_offset = 0;

{

auto& s0 = inject_request.symbols(0);

CHECK(s0.relative_function_ptr() != 0);

CHECK(not inject_request.first_symbol_str().empty());

void* func = dlsym(patch, inject_request.first_symbol_str().c_str());

CHECK(func != nullptr);

fn_ptr_offset = bit_cast<long>(func) - s0.relative_function_ptr();

}

patches.emplace_back(patch);

for (auto& p : inject_request.symbols()) {

long fn_ptr = p.relative_function_ptr() + fn_ptr_offset;

auto& sym = symbol_fn_ptrs[p.symbol_hash()];

for (auto& old_fp : sym) {

printf("Setting Redirect from old_fp (0x%lx) to p_ptr (0x%lx)\n",

old_fp, fn_ptr);

std::cout << std::endl;

SetRedirect(old_fp, fn_ptr);

}

sym.push_back(fn_ptr);

}

return true;

}Unit Tests

See how output of F is changing at runtime.

// f.cpp

int F(int x) {

return x+10;

}// runtime_inject_test.cpp

int F(int x);

TEST(RuntimeInjector, Basic) {

InitInjector(argv_gtest[0]);

EXPECT_EQ(11, F(1));

EXPECT_EQ(13, F(3));

ASSERT_TRUE(Inject(Compile(R"(

int G() {

return 8000;

}

int F(int x) {

return x + 100;

}

)")));

EXPECT_EQ(101, F(1));

EXPECT_EQ(103, F(3));

ASSERT_TRUE(Inject(Compile(R"(

int G();

int F(int x) {

return x + 1000 + G();

}

)")));

EXPECT_EQ(9001, F(1));

EXPECT_EQ(9003, F(3));

ASSERT_TRUE(Inject(Compile(R"(

int G() {

return 10;

}

)")));

EXPECT_EQ(1011, F(1));

EXPECT_EQ(1013, F(3));

ASSERT_TRUE(Inject(Compile(R"(

#include <string>

int SumOfDigit(const std::string& s) {

int p = 0;

for (char c : s) {

p += c - '0';

}

return p;

}

int F(int x) {

return SumOfDigit(std::to_string(x));

}

)")));

EXPECT_EQ(12, F(453)); // sum of digits : 4 + 5 + 3 = 12

EXPECT_EQ(10, F(136));

EXPECT_EQ(45, F(136873737)); // 1 + 3 + 6 + ... = 45

ASSERT_TRUE(Inject(Compile(R"(

#include <string>

int SumOfDigit(const std::string& s) {

// returns sum_of_digit + length of string

int p = 0;

for (char c : s) {

p += c - '0';

}

return p + s.size();

}

)")));

EXPECT_EQ(15, F(453));

EXPECT_EQ(13, F(136));

EXPECT_EQ(54, F(136873737));

}